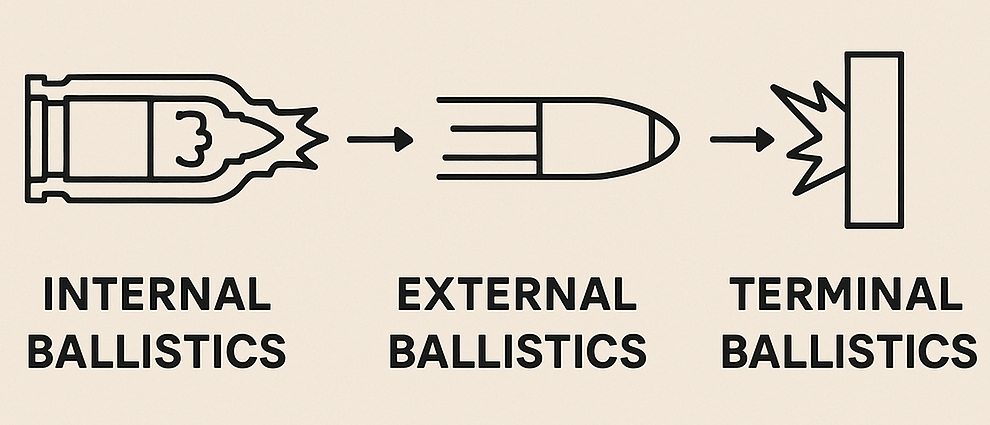

Ballistics is commonly the most complicated part of shooting, and the farther you dive into it, the more complex it gets. To make things a bit easier, we split different portions of ballistics into separate terms. After the blanket term “ballistics”, we can narrow our focus to internal ballistics, external ballistics, and terminal ballistics; instead of one complicated topic, you get to learn three! Don’t worry though, ballistics is not all that hard to grasp, and after a few minutes reading here, you will know more than enough to make a difference in the field.

Here is a high level summary before we dive into the details,

Internal ballistics studies the projectile while it’s still inside the firearm and is most important to gunsmiths. External ballistics covers the flight of the projectile, and matters most to long range shooters. Terminal ballistics studies how a projectile impacts its target, and is most important to hunters.

Internal Ballistics – Gunsmith’s Playground

Put simply, internal ballistics is the ballistics of a projectile while it is still inside the firearm. This includes everything from the moment the primer is ignited, to the moment the bullet leaves the end of the barrel. Although there is plenty that happens between those two points, and the amount of energy the projectile gains during the internal phase of ballistics heavily affects how it performs in the later phases.

Internal ballistics matters most to the gunsmiths. Cartridge design, chamber pressure, barrel design, and other factors gunsmiths geek out over heavily influence internal ballistics. Careful tuning of these parameters is how they ensure a firearm can perform for decades instead of exploding into pieces on the first shot. After ensuring a firearm will perform on a basic level, their design choices also change what the firearm is best used for, or how expensive it will be to produce.

Barrel length and barrel twist rate are two factors that are going to be vital for ballistics phases down the line. We have seen recent cartridges like the 8.6 Blackout that have incredible 3:1 spin rates, which gave it the ability to be subsonic while still carrying a large amount of rotational energy and dumping a large amount of that energy onto the target quickly.

Meanwhile, shooting the exact same cartridge out of a shorter barrel will lead to the projectile carrying less overall energy once it transitions to external ballistics, but the trade off may be worth it to have a more maneuverable firearm. There are thousands of design choices a designer could make, and the majority of them influence internal ballistics, cascading down to future ballistic phases.

External Ballistics – Serious Shooter DOPE

External ballistics picks up right where internal ballistics leaves off, as soon as the bullet comes out of the barrel. External ballistics is the study of everything that happens to a projectile in the air, from source to target. This is where things like gravity, wind, and even the Earth’s spin can have an effect. This is also the type of ballistics that most people think about when they think of the term “ballistics”. It is also the most math heavy, but you can find a calculator online for nearly every situation.

The starting point for external ballistics is “muzzle energy” (or kinetic energy), which is the amount of energy a bullet has at the muzzle of the firearm. Muzzle energy is calculated with linear velocity and the mass of the projectile. Then, if you know how your bullet is designed and what its ballistics coefficient is (how well it avoids air resistance / drag), you can take these three terms and plug them into a ballistics calculator to get a good estimate of how far your bullet will drop by the time it gets to your target.

The shape of your bullet is what affects your ballistic coefficient, flat nose bullets will have more drag than pointed bullets, and will not fly as far; all else equal. Your spin rate is also important, as without spin the bullet would tumble and not fly true. Although the more spin you have for an input energy, the less linear velocity you will have, so the sooner your projectile will hit the ground. Weather and the wind also play a role, especially if you are shooting extreme distances. External ballistics can be as complicated as you want it to be, but what most people care most about is bullet drop.

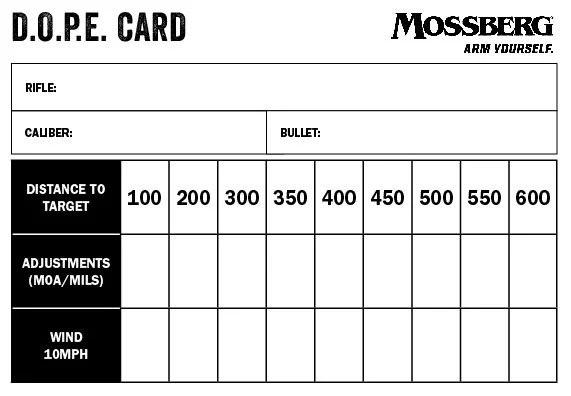

Bullet drop is crucial information for long range or competitive shooters. Knowing exactly how much your bullet is going to drop for a given range is worth more than gold to many shooters. The science is well defined, but getting all the input values perfect is a challenge, if not impossible. So many shooters gather this data experimentally and develop a Data On Previous Engagements (DOPE) chart. That way they can look at a chart before shooting and know that their bullet drops an average of X every time they shoot Y distance; avoiding on the fly calculations.

While most hunters do not need to worry about bullet drop, those that shoot over a couple hundred of yards regularly do. These guys are often as serious if not more serious about their DOPE than sport shooters. Spending the whole season getting to a point where your target animal is 300 yards away and then missing 20 yards low is simply unacceptable.

Terminal Ballistics – Hunter’s Obsession

Terminal ballistics is the study of how a projectile impacts its target. This is where we pay special attention to how much energy the projectile has, and how quickly it is going to dump that energy into the target. Of course, internal and external ballistics heavily influence terminal ballistics. The more energy those two stages of ballistics can add to terminal ballistics, the more powerful the projectile is going to be at the target. While important, the strategy behind the construction of the bullet cannot outperform receiving more energy from the internal and external ballistic stages, in a general sense.

The construction of a bullet can impact multiple stages of ballistics, but most commonly terminal ballistics. Cone shaped bullets made of harder materials are made to penetrate the target and keep going. Flatter softer bullets are made to expand and stop when hitting a target, transferring as much of its energy as possible. These are two extremes, and you will find all sorts of in between cases. In general, there is plenty of room for engineering strategies that achieve different goals during the terminal ballistic stage.

Some of the factors that have the largest effect on terminal ballistics are bullet shape (FMJ vs hollow point), sectional density (hard penetrating vs soft fragmenting bullets), and the internal structure (cup and core vs nosler and more). These factors can also affect other stages of ballistics, commonly external ballistics. Whatever design choice you make, there is often a give and take in another area.

The people that care most about terminal ballistics are often hunters. Most hunters don’t often shoot much farther than 200 yards at a live target, so external ballistics is not always a concern. Although how their bullet performs once it hits the target is the cause of many heated debates. No matter how you design a bullet, some hunters will revere it as the best bullet out there, others will say it is useless. Most hunters want a bullet that dumps a large amount of energy into its target quickly, without sacrificing much else. While these design choices are important, the effects on most situations are often smaller than many make them out to be.

Splitting Hairs

When it comes to internal, external, and terminal ballistics, it’s tempting to idolize one over the others, especially depending on whether you’re a gunsmith, a long-range shooter, or a hunter. However, no single stage of ballistics stands above the rest. Each one plays a vital role, and the performance of a projectile is the result of how well all three phases work together.

Internal ballistics sets the foundation. Without a properly functioning firearm and optimal cartridge design, nothing else matters. External ballistics dictates the projectile’s flight and determines whether it can even reach the target accurately. Terminal ballistics is where all the energy and precision either achieve the intended effect—or don’t.

Every stage has its trade-offs. A heavier bullet might perform better terminally, but suffer in terms of drop and drift. A fast twist rate might stabilize a bullet well in flight, but at the cost of muzzle velocity. A soft, expanding bullet might transfer energy better at the target, but struggle with deep penetration. Optimize one aspect, and you often sacrifice another.

Ultimately, good ballistic performance is about balance. Whether you’re tweaking a load, picking a new caliber, or just trying to better understand what’s going on between the trigger pull and the impact, remember this: each stage of ballistics matters, not more, not less, and balancing all three is what takes a firearm from good to great.